The Russian community of Ida–Viru, Estonia

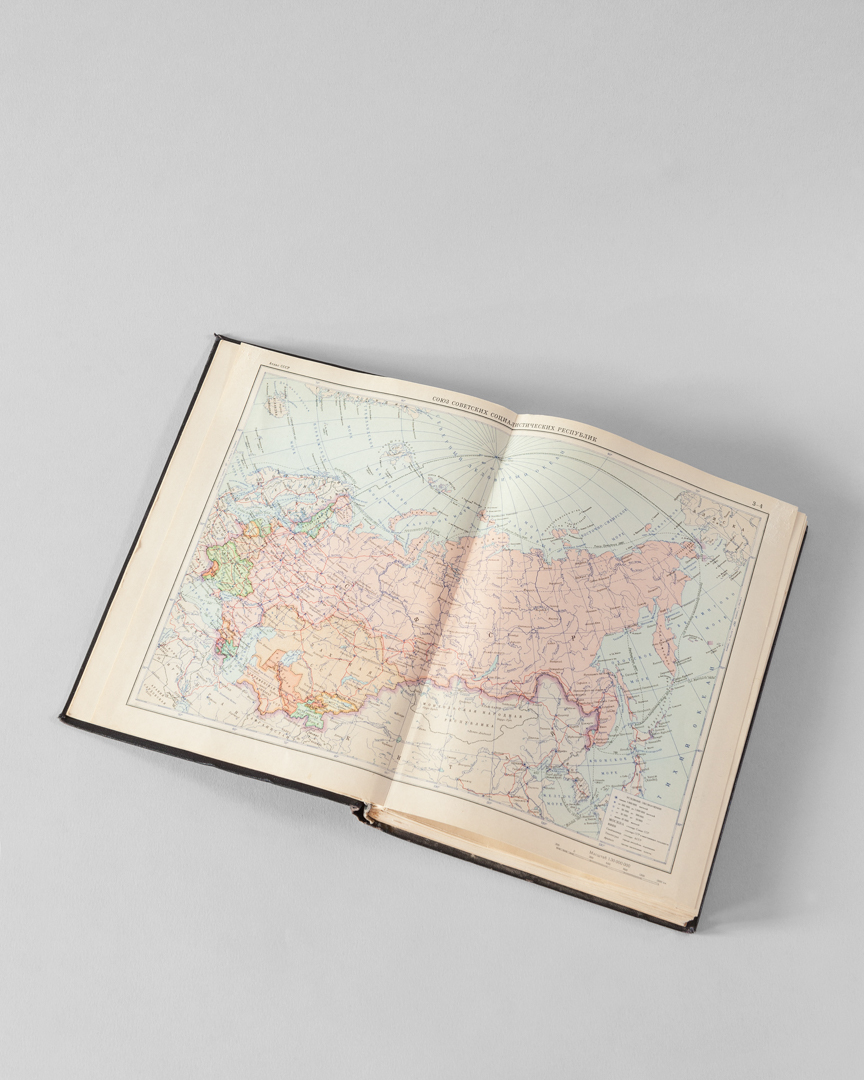

Estonia is the northernmost of the three Baltic States. 1.3 million people live in the country and, as a consequence of 50 years of Soviet occupation from 1944 to 1991, a quarter of them are ethnic Russians. Half of them (moreless 130,000 people) is concentrated in one single county, called Ida-Viru. This little area shares its eastern border with Russia. A very peculiar one, indeed, since it parts far more than two sovereign States: crossing the border (granitsa, in Russian language) means to leave behind both European Union and NATO, of which Estonia is among the most loyal and committed members.

After the outbreak of the Ukrainian Civil War and the unilateral annexation of Crimea by Vladimir Putin in order “to defend Russian-speaking citizens abroad”, experts and strategists raised concerns towards Estonia, and especially Ida-Viru county, as the next possible target of the Kremlin’s brave expansionist policy. Indeed, in the whole EU there is no higher percentage of ethnic Russians compared with total population than the one of Ida-Viru: 73% (with peaks of 85% in the municipalities of Narva and Sillamäe).

After the outbreak of the Ukrainian Civil War and the unilateral annexation of Crimea by Vladimir Putin in order “to defend Russian-speaking citizens abroad”, experts and strategists raised concerns towards Estonia, and especially Ida-Viru county, as the next possible target of the Kremlin’s brave expansionist policy. Indeed, in the whole EU there is no higher percentage of ethnic Russians compared with total population than the one of Ida-Viru: 73% (with peaks of 85% in the municipalities of Narva and Sillamäe).

Here, in July 1993, a referendum was also held: the inhabitants were asked if they wanted the county to be autonomous from the newly declared Estonian Republic. The “yes” vote prevailed but the State Court ruled that the consultation contravened the Constitution and the movement for autonomy was deflated.

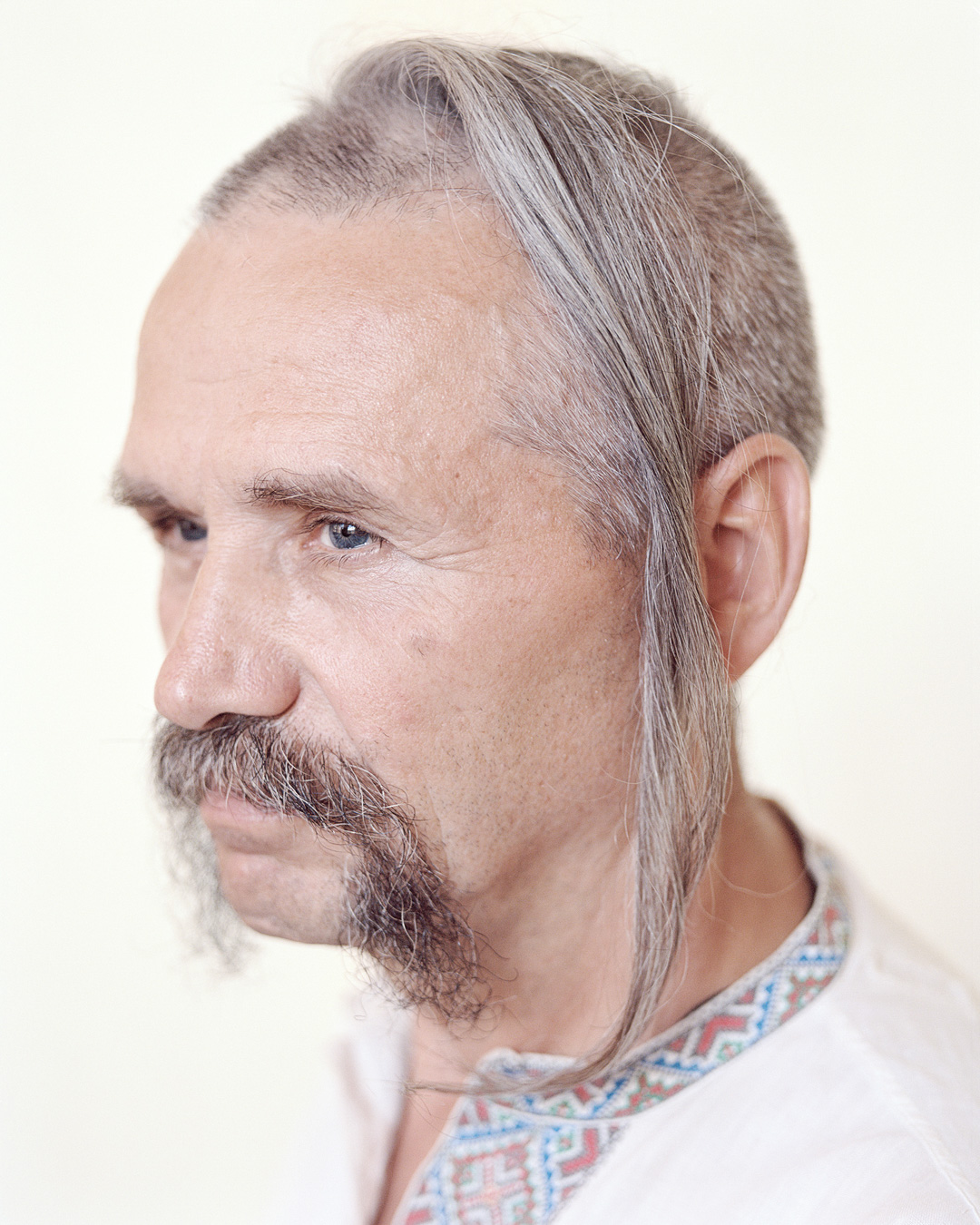

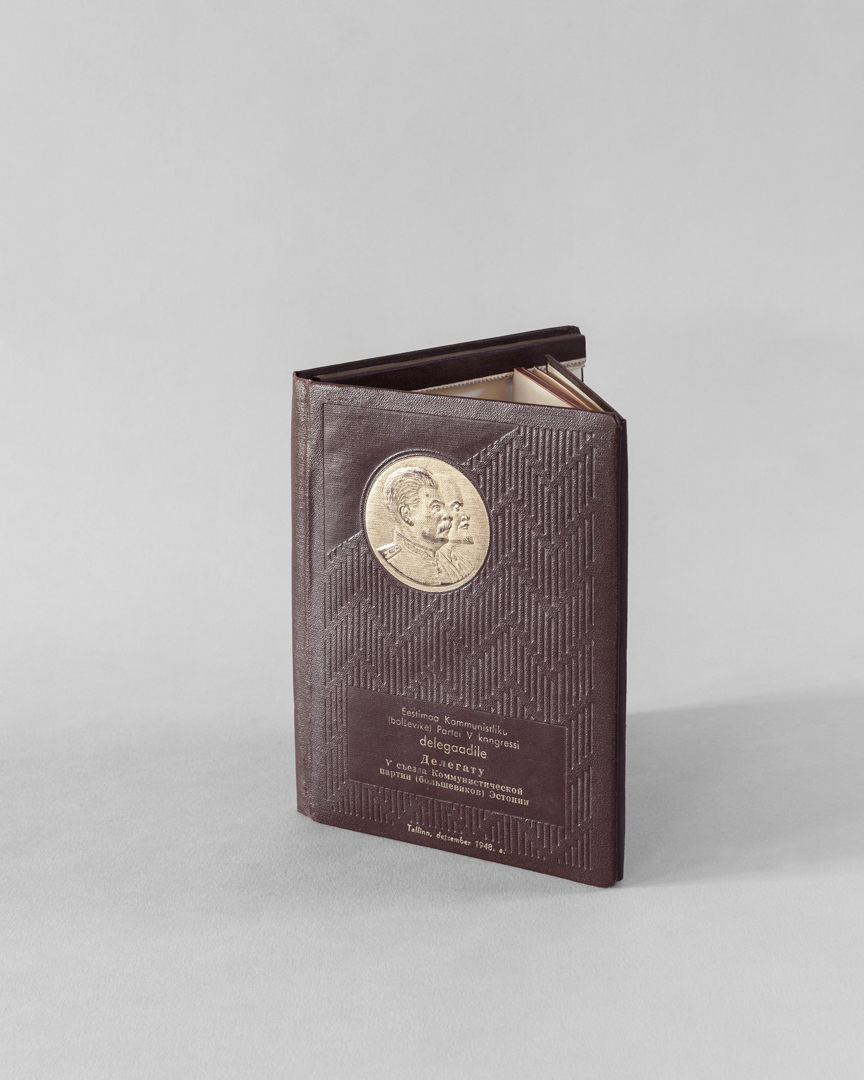

Estonia’s recent past went through a severe process of Russification, started with Stalin in the 50s and ended just after the country achieved the independence in 1991. Since that moment the Estonian government has not yet been fully able to equalize the living conditions of the vast Russian minority to the country average. Today some of the ethnic Russians have chosen to embrace with hope a common future under the Estonian flag, but on the other side there is still a huge number of them who have maintained their Russian citizenship. Furthermore, another significant part of the ethnic Russians (6.8% of Estonia’s population, according to Amnesty International’s 2015 report) are not willing to face the controversial Estonian language and culture “citizenship test” and therefore are living in the Baltic country as stateless persons.

Estonia’s recent past went through a severe process of Russification, started with Stalin in the 50s and ended just after the country achieved the independence in 1991. Since that moment the Estonian government has not yet been fully able to equalize the living conditions of the vast Russian minority to the country average. Today some of the ethnic Russians have chosen to embrace with hope a common future under the Estonian flag, but on the other side there is still a huge number of them who have maintained their Russian citizenship. Furthermore, another significant part of the ethnic Russians (6.8% of Estonia’s population, according to Amnesty International’s 2015 report) are not willing to face the controversial Estonian language and culture “citizenship test” and therefore are living in the Baltic country as stateless persons.

Filippo Bardazzi ©2025